In the previous posts we first looked at how we can generate a sine wave as ‘raw’ floats and interpret them using ffplay. Later we explored how to read / write .wave files and how to extract and create ‘automation tracks’ using breakpoints.

As you might have noticed, we’ve never actually created .wave files from scratch with our own sound data. So, it’s about time to change that. In this blogpost we’ll look at how we can create a variety of basic soundwaves.

The code we’ll be diving into for this post can be found in the Github Examples and as part of the GoAudio library.

Constructing an oscillator

An oscillator is a device (in our case a piece of code) that generates a periodic (oscillating) signal. The sine wave is one example of such a waveform, but we’ll also look at square waves, triangle waves, and sawtooth waves.

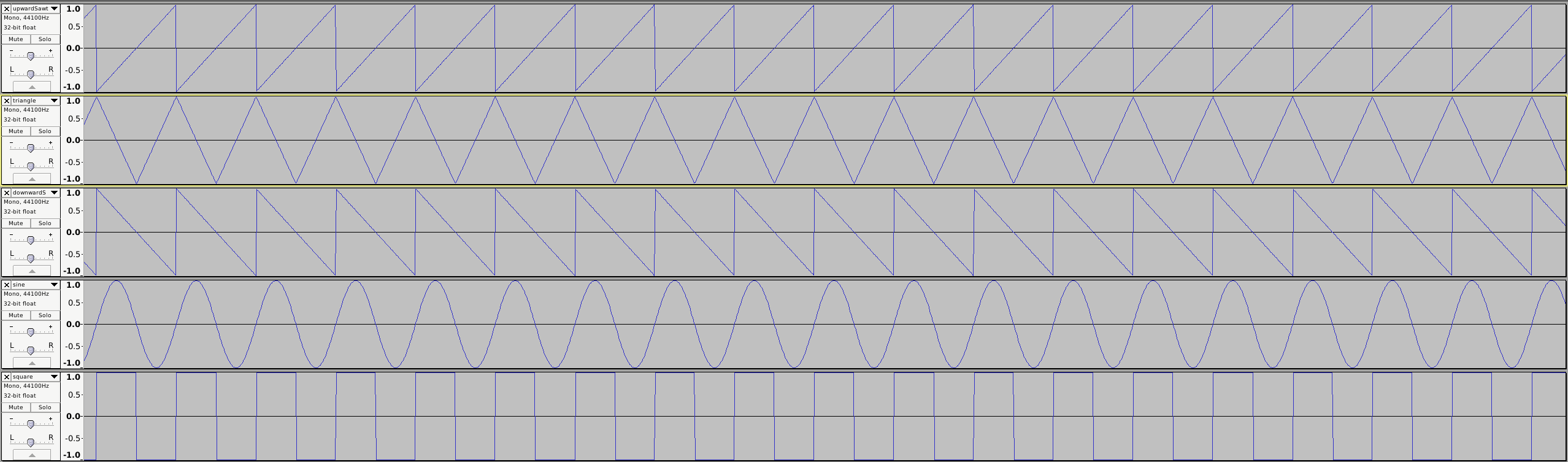

At the end of this post, you’ll be able to generate signals that look like this:

On the images, these look like connected lines, but in our digital audio signal that we will generate, they are separate datapoints. How many ‘points’ do have in each cycle? That depends on the sample rate we are using.

We can figure out how to place our dots given the sample rate. Remember that we are using radians

in our trig functions, and a period of the wave is thus defined as: 2 * PI. To know how to place

our points, we can figure out part of the puzzle (the ‘increment’) as follows:

increment = (2 * PI) / SampleRate

Unfortunately, this is not the entire picture. We also have the keep in mind that our wave has a certain frequency - which we’ll have to account for in our increments. The actual function then becomes:

increment = ((2 * PI) / SampleRate) * freq

In our Oscillator we’ll have to track these things. We’ll want to know what the current frequency

is, what the current phase is, and how to increment this phase to get the next value of our wave.

This solves only part of the puzzle. It’s also clear now that we’ll need a way to differentiate which type of waveform the user wants to

generate. For this, we can start with an “enum” of a Shape type. Each shape will also need to be

calculated in a different way, so we can associate a Shape with a calculation function with a map shapeCalcFunc = map[Shape]func(float64)float64

|

|

These are our ‘elementary’ shapes that we’ll use for the next few posts. Although we’ll extend on them, they’ll give us a solid base to start.

Putting this together, we can define an Oscillator struct:

|

|

Notice that we are storing twopiosr = tau / SampleRate = (2 * PI) / SampleRate as a convenience variable. We’ll be

using this in a few functions.

Generating waveforms

With this constructor, we have the basis for a working oscillator but it’s not yet generating anything. For this purpose we’ll need a function that asks the oscillator to produce the next value of the wave (It can do this indefinitely). This function will need to do a few things:

- Accept a frequency for the wave to generate

- Adjust the increment between frames

- Find the value at this phase

- Adjust the current phase

- Do some bounds checks on the phase (optionally)

Our function in Go becomes:

|

|

The adjustments to our curphase is to keep it in the bounds (Although depending on the

implementation of the sin function this might not be necessary, I kept it here as a guard but I’m

pretty sure it’s not necessary in Go).

Waveforms functions

The only part left to implement is the actual generation of the different shapes of waves. This is

what happens in the call val := o.tickfunc(o.curphase). By using a generic function call, we can

inject the correct calculation function in the call to NewOscillator().

The easiest one to implement is the Sine wave.

|

|

A close contender for being the most simple to implement is probably the square wave function. In

this case, half our period is 1 and the other half is -1.

|

|

The triangle wave is the first one that looks more complex, with the sawtooth waves being related to it (you can visually see a sawtooth is being part of the triangle with a sharp cut-off.

|

|

Making waves

With our oscillator set up, we can finally start using it. All the code that follows is contained in this GoAudio example. The setup of this example is similar to what we’ve seen in the previous posts where we deal with parsing breakpoints. To keep things simple, this entire setup happens in our main routine.

|

|

Notice that we also print the usage, this tells us that we expect a duration, a shape, amplitude breakpoints, frequency

breakpoints and finally an output file. The ‘heavy lifting’ happens in the call to the generate

function. Here we pass along the duration, a Shape instance derived from the string entered on the

CLI, our breakpoints and finally also a WaveFmt. Remember that the WaveFmt struct contains the

metadata for the .wave files we are generating. In this case, the statement wave.NewWaveFmt(1, 1, 44100, 16, nil) means it’s a standard PCM wave-file, with 1 channel (mono) playing at 44.1Khz,

where the data consists of 16-bit floats. You can play with these values to see how the result

changes. (Well, the channels are a bit trickier to change as we learned in this

post).

Finally in the generate function, we need to calculate the amount of samples (= frames for mono) we

need to generate. Then we’ll call the Tick function of our oscillator as well of our breakpoint

stream to continously retrieve the next value.

|

|

And there we go, we now have all code in place for generating basic waveforms. When examining them in audacity we get the result shown at the beginning of this post.

Improvements

With this we can generate basic “clean” audio signals, this could be handy for testing purposes but as far as I know it pretty much ends there. (Most software synths will also let you play around with these type of waves, but you’ll tweak them to something more usable).

You might have some concerns with this code though, the first being the performance issue. An oscillator is by definition something repetitive, yet we are constantly calculating the ‘next phase’. Is this strictly necessary? No, we can actually store the values we expect to see in a ‘lookup table’. (As a complete side-note here, this always reminds me of how in WW2 they used ‘firing tables’ to lookup ballistic trajectories. More on that here)

In the next post we’ll take a look at using lookup tables, and we’ll also start thinking about harmonics to represent sound in a more realistic way.

Resources

If you liked this and want to know when I write new posts, the best way to keep up to date is by following me on twitter.