In our last post we have looked at how we can create a simple binary sound file. By creating a sine wave with exponential decay, we can get the effect of a single note playing.

It’s good to know what these types of files look like. In the real world however you’ll usually

encounter files that are a bit more complex. One of the common formats to find audio in is the WAVE

file format, normally denoted with the extension .wav or .wave.

In this post we will learn how to extract information from this file, and how to write our own audio data to a wave file. This will form a base for future posts in which we can start manipulating this audio data.

As usual, all code can be found on GitHub, albeit in a separate library this time. If you want to know how to manipulate the audio itself rather than dealing with writing the files, the next blog post will do just that.

What’s in a wave?

WAVE is the ‘WaveForm Audio File Format’, developed jointly by IBM and Microsoft in the early 90s. A wave file stores audio data as samples (double precision) along with metadata describing what to expect from the audio stream, such as the amount of channels (mono, stereo, surround..), the amount of samples, etc..

Usually the encoding uses PCM, Pulse-Code Modulation. Whilst not immediately necessary for understanding this blog, the code will refer to PCM in various places. For simplicity’s sake we’re going to assume that every file is encoded like this.

Anatomy

Let’s break down the content of a wave file step by step.

Header

The first part of the wave file is a header. Viewed as HEX you will recognize this by the values “RIFF” and “WAVE” that stand out. For example, this is the first line of my hex editor when I open the hex output of a wave file:

00000000: 5249 4646 1028 0200 5741 5645 666d 7420 RIFF.(..WAVEfmt

This single line tells us a few things that are useful. First, RIFF means it is written using little-endian, otherwise it would have been RIFX. Secondly, the WAVE and fmt message tells us that at least those parts of the files are generated correctly.

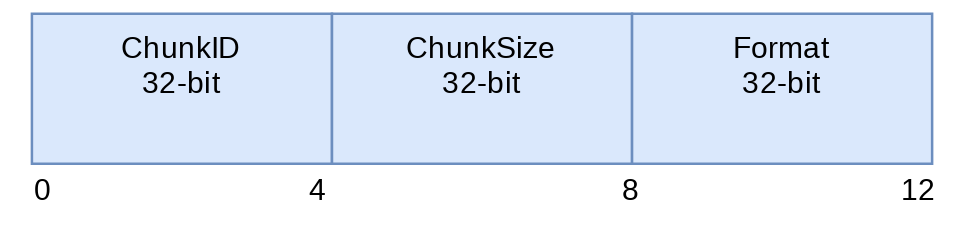

The wave header principally exists out of three components, a chunkID, a chunk size and a

format. The format should always be WAVE for our wave files. Below is a schematic representation

of the wave header with the byte offsets anotated, as well as the size in bits.

Fmt

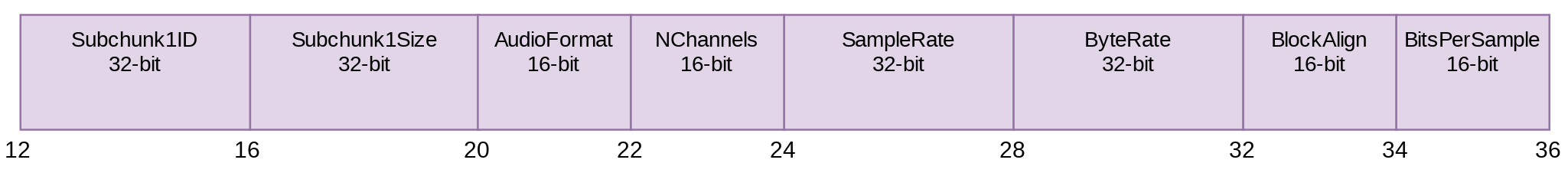

Apart from the header, the wave file exists of two subchunks. One is for metadata, it describes how the audio data in our file is going to look like. The second subchunks contains the raw audio data itself.

Below is a representation of this ‘fmt’ chunk:

(perhaps better to open this in a new window.

Briefly explained, it contains:

- Subchunk1ID: This should contain

fmt. - Subchunk1Size: Size of the fmt chunk

- AudioFormat: PCM usually, indicated by the value

1 - NumChannels: 1 = mono, 2 = stereo, ..

- SampleRate: 44100, 48000, ..

- ByteRate: SampleRate * NumChannels * (BitsPerSample / 8)

- BitsPerSample: 8, 16, 32,…

Data

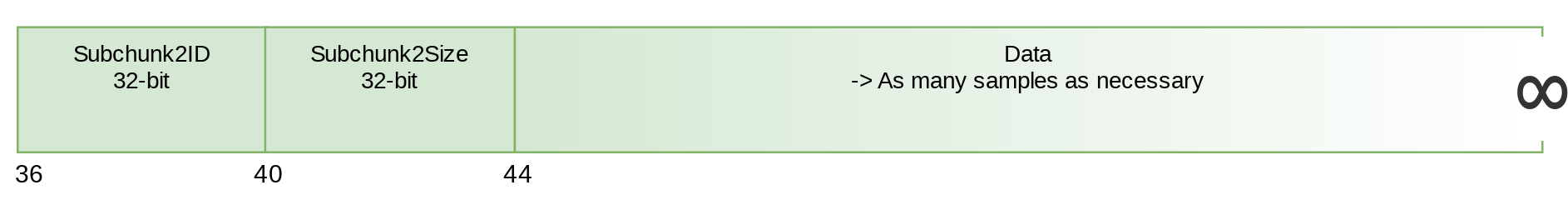

The final part of the wave file contains our actual raw audio samples, as well as two extra fields.

The first field is the Subchunk2ID, this should contain the value data. And secondly the

Subchunk2Size, which is the byte-size of the data. Finally it also contains the raw audio data

samples.

The code

Wave Reader

The key parts of the code for reading and writing WAVE files are all about how to transform our bits into actual data. We will either have to transform data to floats or to ints depending on the chunk field.

For writing a 4 byte piece to int we can use the following code:

|

|

Next we can use this for floats as well.

|

|

Using these functions we can then combine those into an actual reader.

|

|

Here we can see how we check for both the RIFF and WAVE content in the header to make sure that

these are present in the correct shape.

And perhaps more crucially, we need to read the raw audio data.

|

|

All chunks follow a similar pattern, and can all be found on GitHub

Writer

For writing, the key functions for reading are just reversed. We take an int or float and turn this into a byte slice.

For writing our int32 to bytes:

|

|

And similarly we could write float64s:

|

|

The most crucial part here is writing the raw audio samples, with these helper functions this would look like:

|

|

What’s next?

Now that we have this library, the next blogpost can dive into how we can use this to manipulate .wave sound files.

If you enjoyed this and want to know when I write new posts, consider following me on twitter.