Audio from scratch: generating sound

In my ‘audio from scratch’ series we will take a look at various ways in which we can manipulate audio data with Go. We’ll look at the anatomy of a wave file, how to apply stereo panning, converting mono files to stereo, how to work with breakpoint files through linear interpolation, etc.

But, in this post we’ll be using Go to create sound from scratch in binary format. The end result of this post is to play a sound of a certain frequency, sample rate and duration. We’ll also apply an exponential decay so the sound will taper off. In the end, the sound should become the one from this video:

Step 1: What the sound?

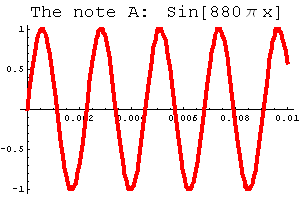

In it’s most simple form, sound to a computer can be thought of as a simple wave encoded digitally. Before the sound reaches your ears it goes through a digital to analog converter, essentially translating the digital signal to a current for your headphones / speakers. For example, note A would look like this:

(source: http://www-users.math.umn.edu/~rogness/math1155/soundwaves/)

(source: http://www-users.math.umn.edu/~rogness/math1155/soundwaves/)

As a first step, let’s try to just create a sine wave with go. We can generate this using math.Sin(x) and pass x as radians. We’ll have to iterate over a range to get the sine wave out of this. To stay in the realm of audio programming, the amount of ‘points’ that we’ll plot to the sine wave are our samples. (If you want to skip ahead, all code for this post is on github: https://github.com/DylanMeeus/MediumCode/blob/master/Audio)

const nsamps = 50 // samples to generate

func generate() {

tau = math.Pi * 2

var angle float64 = tau / nsamps

for i := 0; i < nsamps; i++ {

samp = math.Sin(angle * float64(i))

fmt.Printf("%.8f\n", samp)

}

}

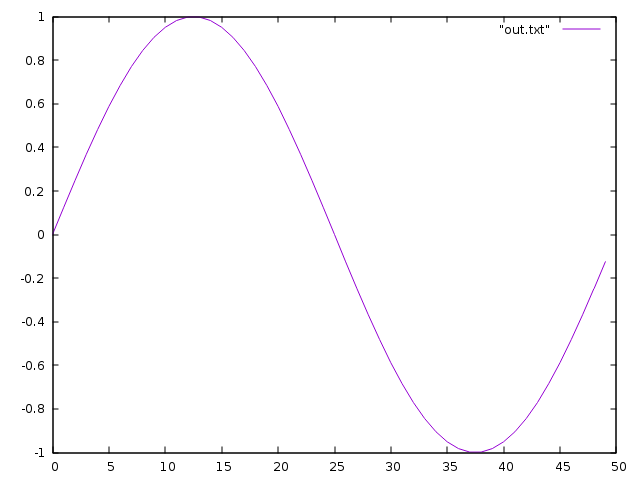

Notice that we print the sample to stdout, we can pipe this output to a file (go run main.go > out.txt) . The output in this file will look like this:

-0.00000000

-0.12533323

-0.24868989

-0.36812455

-0.48175367

-0.58778525

.. Kind of hard to see what’s going on here. But using gnuplot we can visualize this file easier. In gnuplot, run:

plot "out.txt" with lines

This looks like a perfectly continuous sine-wave, but that’s the way gnuplot is visualizing it “with lines”. If we plot the bars we can see a slightly different view. ( plot “out.txt” with boxes )

Now that we can generate sine-waves, we have the basics of how we can make sound. Although this is just floating point numbers at this point, we can actually turn this into something playable as a raw audio file.

Step 2: Generating sound

To turn this sine wave into an actual sound we’ll have to introduce a few things.

Sample Rates

Firstly, sound is stored at a certain sample rate. A sample rate tells you how many samples per second are used to encode your sound. A CD-Quality recording has a sample rate of 44100 hertz, allowing for a frequency of up to 22.05KHz. Considering the human ear hears sound between 20Hz to 20KHz, this is plenty (Assuming you’re only targetting human listeners 😛). Although other formats are possible, such as 48Khz for DVD-Video quality or 96KHz for DVD-Audio quality, we’ll stick with CD-Quality for now. As you will see — changing this would be trivial however. Feel free to play around with this yourself to see if you can hear a difference in sound. So instead of using our nsamps = 50 we’ll need at least 44100 samples. To adjust the duration of the sound we’ll also add a variable for this.

const (

Duration = 2

SampleRate = 44100

)

Frequency

Next, we’ll introduce a frequency. For now we will use a frequency of 440Hz which is defined as the “pitch standard”. It’s the standard tuning of musical note A above middle C. To not diverge to much of our goal to generate music, just check this wiki page if you’re curious as to why we are using this frequency. Adding this we’ll expand our consts again:

const (

Duration = 2

SampleRate = 44100

Frequency = 440 // Pitch Standard

)

Storing sound

We now have the basic ingredients for generating sound, but we miss one vital part. How can we store this data so our computer can interpret it as sound? Our floats that we generated in step 1 can indeed be used, but we will have to store them as a binary representation. One tricky part here is that you have to store them in a way your computer can read them — meaning you’ll have to use BigEndian on a BigEndian machine or LittleEndian otherwise. On a linux system this can be discovered through your terminal (possibly same command on macOS, don’t have one to verify!).

dylan@devuan:~$ lscpu | grep "Byte Order"

Byte Order: Little Endian

The Code!

Now we know what to do, and have our constants set up, let’s revise the generate function to tie it all together. The sound will be stored in a file called “out.bin” on your machine. (For brevity, I have removed error handling!)

func generate() {

nsamps := Duration * SampleRate

var angle float64 = tau / float64(nsamps)

file := "out.bin"

f, _ := os.Create(file)

for i := 0; i < nsamps; i++ {

sample := math.Sin(angle * Frequency * float64(i))

var buf [8]byte

binary.LittleEndian.PutUint32(buf[:],

math.Float32bits(float32(sample)))

bw,_ := f.Write(buf[:])

fmt.Printf("\rWrote: %v bytes to %s", bw, file)

}

}

Using ffplay we can now play this file, although we will need to specify our sample rate and our format. Specifying our showmode we can also visualize the sound being played:

ffplay -f f32le -ar 44100 -showmode 1 out.bin

playing our file using ffplay It sounds like this:

Alternatively you could also use Audacity and import our binary file as a ‘raw audio file’. Just make sure you select mono channel and the correct encoding. 😉 This is how we could create the pitch standard. Although a small improvement would be to tamper the sound near the end. That would feel more ‘natural’ than having a constant signal. To achieve this we can introduce exponential decay near the end of the signal. Extension 1: Exponential Decay We don’t have to add a lot to get the exponential decay. We want to fade out our signal so we’ll define a start and an end ‘amplitude’ to generate a decay factor. Next on each iteration we’ll modify our signal’s actual amplitude by multiplying it with a decay factor. At the top of our function, we’ll define these variables:

func generate() {

var (

start float64 = 1.0

end float64 = 1.0e-4

)

nsamps = Duration * SampleRate

decayfac := math.Pow(end/start, 1.0/float64(nsamps))

..

Once we have them set up, in our loop for generating the wave we can just modify the sample on each iteration

sample := math.Sin(angle * Frequency * float64(i))

sample *= start

start *= decayfac

When we put this together, our function becomes:

func generate() {

var (

start float64 = 1.0

end float64 = 1.0e-4

)

nsamps := Duration * SampleRate

var angle float64 = tau / float64(nsamps)

file := "out.bin"

f, _ := os.Create(file)

decayfac := math.Pow(end/start, 1.0/float64(nsamps))

for i := 0; i < nsamps; i++ {

sample := math.Sin(angle * Frequency * float64(i))

sample *= start

start *= decayfac

var buf [8]byte

binary.LittleEndian.PutUint32(buf[:],

math.Float32bits(float32(sample)))

bw, _ := f.Write(buf[:])

fmt.Printf("\rWrote: %v bytes to %s", bw, file)

}

}

And now if we play this sound, we get the sound from the video at the top of this post. 😃 All code is on GitHub: https://github.com/DylanMeeus/MediumCode/blob/master/Audio/FirstSound/main.go